|

Mobilizing Public Health

Turning

Terror's Tide with Science Turning

Terror's Tide with Science

Responding to the September outbreak of terrorism in America,

senior School leadership launched in late October a new comprehensive

public health initiative to tackle the complex scientific, social,

and governmental issues raised by bioterrorism.

"The School recognizes that this is a national public health

emergency. The School has, in many ways, unequaled expertise in

the issues related to the acute and urgent problem of anthrax bioterrorism

and the longer range strategic issues related to all manner of terrorism,"

says Dean Al Sommer, MD, MHS '73. "Whether it comes through

letters or aerosol sprays or poisoning of water or the food system,

it's the responsibility of the School to come to our nation's defense."

In the coming months, more than 60 faculty members will work on

bioterrorism preparedness, devise new technologies for detecting

anthrax, determine the best therapies, study available antibiotics,

and recommend how to best contain outbreaks of anthrax and other

biologic, chemical, and nuclear hazards.

The School has a three-pronged goal of providing a scientific basis

for rational action, timely and accurate advice for the public and

professionals, and training modules for targeted audiences, delivered

by the Web, simulcasts, and CD-ROMs.

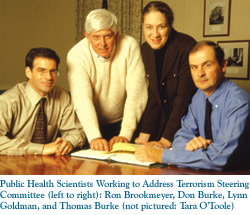

The new initiative, called Public Health Scientists Working to Address

Terrorism (SWAT), will work closely with a related University-wide

effort. Thomas Burke, PhD, MPH, an associate professor in Health

Policy and Management, is the initiative's director. Other steering

committee members include Biostatistics professor Ron Brookmeyer,

PhD; International Health professor Don Burke, MD; Environmental

Health Sciences professor Lynn Goldman, MD, MPH '81; and Tara O'Toole,

MD, MPH '88, the director of the Center for Civilian Biodefense

Strategies. Two to four faculty members from each of the School's

nine departments have been asked to devote the next month or two

to providing immediate input to the effort. The initiative will

draw on the broad spectrum of the School's expertise, including

surveillance, environmental assessment and clean-up, infectious

disease and antimicrobial resistance, vaccine development and testing,

legal issues, disaster management, and communication.

The short-term efforts do not mean abandoning the School's long-standing

research and teaching priorities, according to Sommer. Rather, the

short-term work is a "unique activity in the history of the

School in response to an urgent national need," he says. "I

don't know of any time in the School's history that this has been

done."

Thomas Burke envisions teams of public health researchers, focusing

on specific areas and providing technical assistance and guidance

and help with communication between the government, public health

professionals, and the public. The teams would also bring public

health risk assessment, epidemiology, and other tools to provide

advice on treatment and management of both patients and the "worried

well."

Front-line professionals from across the nation will come to the

School for seminars on the latest knowledge in public health preparedness.

"You bring in the best and brightest to help them understand

the threats and how to attack and ultimately manage them,"

Burke says.

A former deputy commissioner of health in New Jersey, Burke has

seen firsthand the decay in the public health infrastructure through

his work and research for reports by the Pew Environmental Health

Commission and the Institute of Medicine. He recently secured a

$1 million grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

to design a center of excellence in environmental health practice.

"Right now, the School has all these pockets of expertise,"

Burke says. "The task is to pull them all together." -

Brian W. Simpson

Danger in the Dust

It

is 4 a.m. in New York City as four researchers from the School enter

the site of the World Trade Center disaster on foot. Each is lugging

from 50 to 90 pounds of air-monitoring equipment onto Ground Zero.

In the dark, the tangled pile of wreckage takes on a distinctly

hellish cast. It

is 4 a.m. in New York City as four researchers from the School enter

the site of the World Trade Center disaster on foot. Each is lugging

from 50 to 90 pounds of air-monitoring equipment onto Ground Zero.

In the dark, the tangled pile of wreckage takes on a distinctly

hellish cast.

"Fires are still actively burning and the smoke is very intense,"

reports Alison Geyh, PhD. "In some pockets now being uncovered,

they are finding molten steel."

Geyh, an assistant scientist with the School's Department of Environmental

Health Sciences (EHS), heads the team of scientists sent by the

School in response to a request by the National Institute of Environmental

Health Sciences for a coordinated study of the disaster's potential

health effects to those in the immediate environment. By attaching

personal air monitors to the workers and by placing stationary air

sampling pumps outside the periphery of Ground Zero, Geyh (pronounced

"Guy") and her colleagues can determine the density of

the particulate matter in the air, the size of those particles,

and any short-term health effects to those at and around the site.

"This is an incredible situation," she reports. "The

recovery and clean-up efforts are going on around the clock. Hundreds

of people are at the site every day; and many of them have been

there since Sept. 11. Workers at the site want to know what they

are breathing and what to do to protect themselves."

This project is

"clearly among the most energy-draining experiences

of their lives."

- John Groopman

|

Since the drivers and equipment operators are working in two 12-hour

shifts, the researchers must start early and stay late. "None

of the monitors can be left out overnight," says Geyh, "so

around midnight we retrieve everything and take the equipment back

to the hotel, where we recalibrate it before going to bed."

The whole thing recommences at 4 a.m.

"People have been coming back really frazzled," says John

Groopman, PhD. "It's clearly among the most energy-draining

experiences of their lives." Groopman, Anna Baetjer Professor

and chair of EHS, knows of no analogous research situation. "The

fact that thousands of bodies are still hidden in the rubble makes

the work very tense [and] changes the tenor of everything."

At every stage of the clean-up operation, plumes of dust and smoke

are sent skyward. The Hopkins scientists are also gearing up to

measure air quality in the nearby neighborhoods and to enter residences

around Ground Zero to collect and study samples of the dust originally

produced by the collapse, which has sifted into buildings throughout

lower Manhattan. - Rod Graham

Henderson

to Lead Public Health Response to Anthrax Attacks Henderson

to Lead Public Health Response to Anthrax Attacks

Drawing on the School's public health expertise, Health and Human

Services (HHS) Secretary Tommy Thompson recruited D.A. Henderson

to coordinate the national public health response to the anthrax

mail attacks and chose Phillip Russell, MD, to be a key vaccine

adviser.

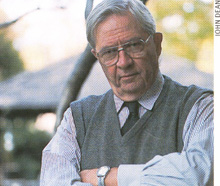

On Nov. 1, Henderson, MD, MPH '60, was named director of the Office

of Public Health Prepared-ness, which will coordinate the HHS responses

to public health emergencies. In taking the job, Henderson leaves

his position as director of the School's Center for Civilian Biodefense

Studies. (See Center story on page 10.)

Henderson, who served as dean of the School from 1977 to 1990 and

directed the global smallpox eradication campaign prior to that,

will coordinate HHS agencies' response to the anthrax attacks and

any possible events in the future. He will continue to lead a national

advisory council on public health preparedness, to which he was

appointed in October.

Russell was named by Thompson to be special adviser on vaccine development

and production at HHS. Russell is a professor at the School's Center

for Immunization Research and has a joint appointment in the School's

Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology.

Tara O'Toole, MD, MPH '88, formerly deputy director of the Center,

has been named to succeed Henderson as director of the Center for

Civilian Biodefense Studies. Thomas V. Inglesby, MD, was promoted

from senior fellow to deputy director of the Center. - BWS

The New Preparedness

As director of New York City's Office of Emergency Management until

last year, Jerry Hauer spent four years preparing the city for a

panoply of natural and man-made disasters.

But the World Trade Center attacks that killed thousands created

a horror that few could ever have envisioned. "A disaster of

this magnitude is a daunting task, no matter what you do in preparation,

no matter what city it is, what the location is," says Hauer,

MHS '78.

Hauer has seen much of the preparedness work he did help the city

through the Sept. 11 crisis. Mutual aid agreements he designed with

neighboring cities and states brought in ambulances from four states

and firefighters from all over.

Currently a senior adviser to Health and Human Services Secretary

Tommy Thompson, Hauer has spent the last few weeks in meetings,

and working on national plans for responding to terrorism involving

biological, chemical, or conventional weapons.

While many in the post-Sept. 11 world have recognized that the nation's

hospitals are ill-equipped to deal with a sudden surge of sick and

injured, more is needed than just additional hospital beds, according

to Hauer. "Beds are great, but if you don't have a surge in

medical staff, how are you going to treat all these people?"

he says. "Surging medical care staff and surging logistics

and infrastructure are bigger components." - BWS

The Ultimate Midterm

In early October, John Agwunobi, MD, MBA, a student in the School's

Web-based MPH (iMPH) program, e-mailed his professors to request

a slight extension on a midterm examination. Considering that he

had been newly appointed as the secretary of health for the state

of Florida — and was busy forming a health response to the

nation's first anthrax case since 1974, Agwunobi's request was granted.

Florida's acting secretary of health since Sept. 1, Agwunobi spent

his first official day as secretary on Oct. 4, which was his birthday

as well. It was also the day he received a call about a "suspicious"

case involving Robert Stevens, a photo editor at a Florida tabloid.

Stevens eventually died as a result of inhalation anthrax, which

catapulted the nation into a frenzy of concern about bioterrorism.

In the midst of organizing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

teams and collaborating with federal health officials, Agwunobi

has had to keep up with schoolwork. "My classes keep me up

most nights, studying and reading," he says, "but I'm

determined to finish my degree, despite these challenges, because

it's so important — more than ever — to have the formal

tools of public health.

"Public health training gives me a whole new perspective on

analysis and problem solving, which is essential in my role here

at the health department," Agwunobi says. "Many of the

principles I'm currently studying, I'm using every day."

- Susan Muaddi Darraj

Next Page >>

|